building the cathedral

notes on politics and vision

Maturity is the ability to live fully and equally in multiple contexts; most especially the ability, despite our grief and losses, to courageously inhabit the past the present and the future all at once. The wisdom that comes from maturity is recognized through a disciplined refusal to choose between or isolate three powerful dynamics that form human identity: what has happened, what is happening now, and what is about to occur.

—David Whyte

one: ISO political lexapro

About a year ago, I was chilling with Grace at my frequent haunt dear friend books, drinking a glass of something good, talking about a whole crab’s bucket of things. At some point the conversation turned to the subject of failure (politically speaking). Grace wanted some of the people in her life to do more and better inhabit their values. To be more politically empathic, active, decent—including, in some instances, to her. “I feel you,” I said, and then added, somewhat tactlessly, really, “but also, almost everyone is so politically depressed right now.”

Political depression was a term I’d stumbled towards in trying to name the mixture of sorrow, distress, numbness, and nihilism that I was seeing again and again in flashes in the leftist and left-leaning people around me. It was marked by a sense of system immovability and stasis, a deeply-felt understanding that bad things were happening and would continue inexorably to happen, and most of all, a profound negative belief in one’s value and agency as a political subject.

And I wasn’t immune myself. I’d spent a ton of 2021 and 2022 feeling so numb and wan, wanting often to check out of everything and never read the news again, let alone continue doing intensive organizing work.

The writer Shadi Hamid reported last year in The Atlantic that according to a 2022 peer-reviewed study, 85 million Americans suffer from politics-driven emotional problems, from depression to insomnia.

The study’s author, the political scientist Kevin Smith, found that 40 percent of American adults reported that politics was a “significant source of stress” in their lives. 5 percent of his sample, which Smith extrapolates to 12 million Americans—reported suicidal thoughts due to politics. Hamid goes on to note that this is most noticeable in young people, and then adds:

“Some observers insist that smartphones are the culprit, but smartphones are ubiquitous in all advanced democracies. In another study, politically induced mental and physical symptoms appear to be more pronounced among not just the young, but specifically those who are politically engaged and left-leaning.”

Hamid’s essential advice: don’t consume news about things you have no agency or control over that make you feel bad. This view, certainly not restricted to Hamid, is glib and lazy. It’s certainly possible to torture yourself by consuming news of distressing current events in a particular valence, to work yourself into an operatic lather that makes you, among other things, unfit to do anything materially useful for anyone anywhere in any context. Our brains were not designed to take in most of the information we do, including news, the way that we take in information currently, yes, sure, sure.

But advising the residents of the richest, most powerful nation in the world order, to just, perennially, ignore current events, to just vibe through it all so as to, I don’t know, not be kept from shopping, is grotesque when you consider it in most applied senses.

Though I was exasperated at the idea that the best response to a genuine social problem (political depression) was self-care TM via indefinite head emptiness, I didn’t have so many silver-bullet counterproposals either.

What I believed then and believe now is that people could attempt to be conscious and engaged, in a variety of ways, particularly through belonging to member-based organizations, or helping build them. For ordinary working people, social power is only to be found in collective entities and acts. This is doubly significant in a capitalist state organized heavily around extreme horniness for individualism and consumption.

But! While I identify primarily a little ole writer of fiction, I also have been part of organizations and outfits formal and informal; I have at least on a couple occasions founded them, and this keeps me from being so very starry-eyed about joining them as some perfect panacea for everyone. Political organizations, radical and 2% and skim, are only as good as their people. If you can join one, or help build a good one, that is wonderful and so deeply needed. Please do. And I think it’s also fine to be honest and assert that outside of some unions, the American left does not have bucketloads of stable organizations with the capacity to absorb masses of people at varying states of emotional and political development—to say nothing of people who are time-or-cash strapped. If that sounds like an indictment, baby, it is.

two: the kind of people who can act

This was around the time I read my boy Mark Fisher writing about his long struggles with depression. Among other things, he notes (italics my own):

The dominant school of thought in psychiatry locates the origins of such ‘beliefs’ in malfunctioning brain chemistry, which are to be corrected by pharmaceuticals; psychoanalysis and forms of therapy influenced by it famously look for the roots of mental distress in family background, while Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is less interested in locating the source of negative beliefs than it is in simply replacing them with a set of positive stories. It is not that these models are entirely false, it is that they miss – and must miss – the most likely cause of such feelings of inferiority: social power.

Fisher then zooms out to assert:

We must understand the fatalistic submission of the population…as the consequence of a deliberately cultivated depression. This depression is manifested in the acceptance that things will get worse (for all but a small elite), that we are lucky to have a job at all (so we shouldn’t expect wages to keep pace with inflation), that we cannot afford the collective provision of the welfare state. Collective depression is the result of the ruling class project of resubordination. For some time now, we have increasingly accepted the idea that we are not the kind of people who can act.

So what could change this reality? Put otherwise: what comes before acting, before taking action, particularly for the politically depressed person? What might the preconditions for it be?

These were the questions I found myself asking.

This is not me writing to you about how change of the sort we need is made—that’s for another time—but about preconditions for change. What I’m interested in here: the question of vision, of visions.

three: pretend it’s a—

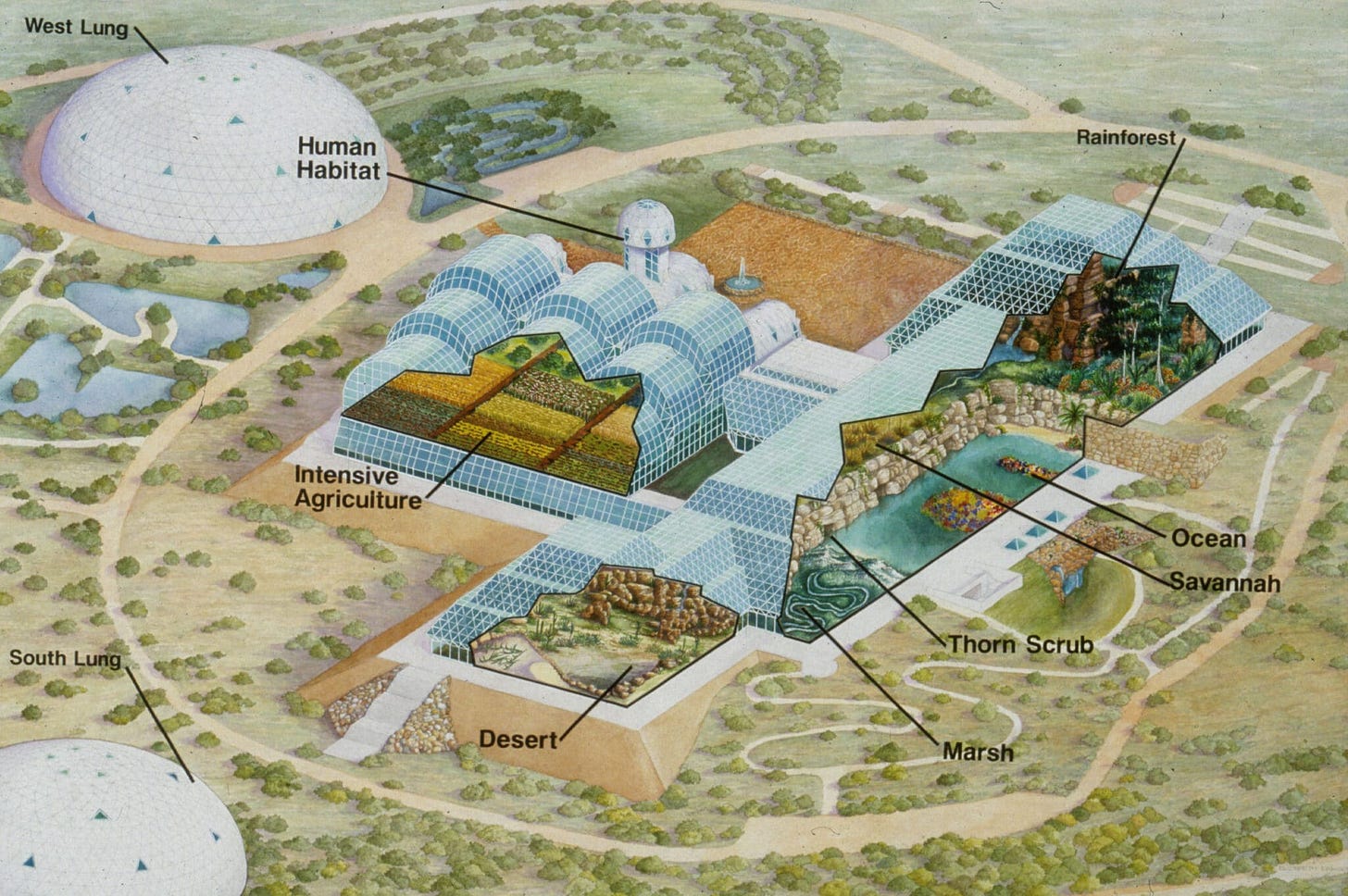

When I was ten or eleven, growing up in the early-aughts Gulf, I tried to design a city. I was a pensive and lonely kid, somehow both hungrily bookish and bad at school, and I was interested at that time by a strange science experiment in Arizona called Biosphere-2, which I knew just enough about then to be inspired by. My city was called, very originally, Biosphere-3. I had taken the only world I really knew, which was the desert city of Muscat, Oman, and encased its mosques and malls in a climate-controlled geodesic dome. I drew mango and lime trees, public swimming pools, flower gardens with benches, huge whirring fans to stave off the quotidian punishing heat. I sketched many libraries, which we did not have and which I yearned for.

Apart from the climate-controlled dome, there was nothing so very utopian about my vision. It was merely eutopos: the good place. Not outopos: the place that in all its flattened and extreme perfection, cannot be.

Something I found poignant when remembering this in adulthood: in my ruled-notebook sketches I laid out how every highway and busy road would have pedestrian bridges, walkways, traffic lights. These were not common in the Muscat of that era, which meant that the simple act of crossing a street could be genuinely scary, especially given the high speed limits of the time. (This is how I ended up crossing a street by myself for the first time in my life in North America post-immigration, in my literal late teens.)

I was a goofy child playacting architect in the back of my school notebooks, but also unwittingly I had drawn a dream of a world that would be kinder to me, allow me and people like me a richer, freer life.

four: the vaccine, the sewer, the cathedral

In telling you the story I did, I suppose my assertion is that most of us need to think before we act, and particularly if the act feels fraught or risky or involves the unknown, this kind of thinking is necessarily imaginative. If you’ve ever applied for something, asked someone pretty out, moved to a different place, you’ve—perhaps without even being so conscious that this was was what you were doing—imagined something different, and then followed your desire.

As best as I can reconstitute the desires of my decades-ago kid self and connect them to my Staedler-pencilled city, I wanted to have some autonomy of movement outside the four walls of my home. I wanted to learn things, perhaps ideally away from the tragicomic tyrannies of the school I was enrolled in. I wanted to be around beauty. I wanted to feel connected to, to be part of, something larger than myself.

I’m now going to talk about something that might seem almost psychotically unrelated to anything: cathedrals.

In the Middle Ages, cathedrals were vital in Europe, serving as places for communal worship, rituals, celebrations, education, and governance. Cathedrals, built with the packed coffers of the Catholic Church during a time when life for the common man was impoverished and short, symbolized local authority and church power. They often acted as social centers akin to city halls.

Cathedrals provided visual education for the largely illiterate masses, who learned about religion through observing the paintings, sculptural art, and architecture within. Cathedrals, from the Latin cathedra meaning chair, were the seats of church power; they were monuments to God's glory, with ornate and towering structures intended to serve as a spatial link to the Divine.

And they took years, and years, and years to build.

This is what I can’t stop thinking about. Workers would spend a lifetime slowly moving a blueprinted structure from foundation stone upwards. Many of them would not live to see the completion of their life’s labor.

Here’s the Cologne Cathedral, built over 632 years (12+ generations) and completed in 1880, when it became the tallest building in the world at the time:

Here’s Ulm Minster, also in Germany, built over 613 years (10+ generations), and the tallest church in the world today, in architectural plan form, and then in one detail shot:

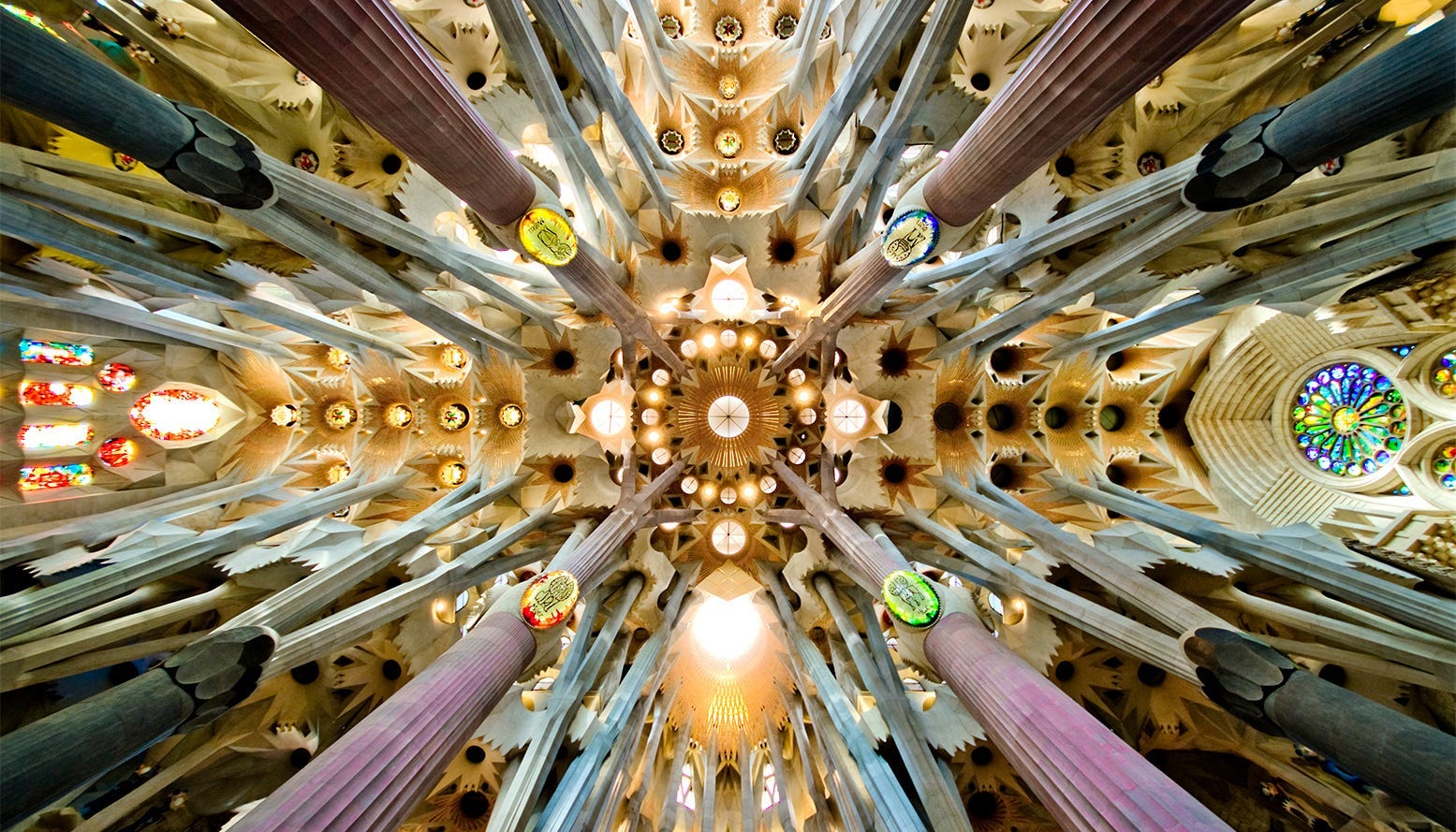

Finally, here’s some details of Antoni Gaudí’s aesthetically groundbreaking Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, begun in 1882 and still under construction, with an estimated completion date of 2026, the centenary of its architect and visioner’s passing. La Sagrada Familia is, as far as I know, the building that has been under construction for the longest time in the contemporary world:

Gaudí, deeply religious, dreamed something in service of his God he knew he would be not be alive to see come to pass. On the subject of the extremely long construction time he said, deadpan, “My client is in no hurry.”

Cathedral thinking is a term used in some circles, including the climate movement, to describe the kind of long-term thinking and steadfast, faithful commitment that is necessary to address our most existential societal problems. It was a concept I first encountered in the philosopher Roman Krznaric’s book The Good Ancestor: How To Think Long Term in A Short Term World. Here are two very brief passages from the book’s introduction:

We are the inheritors of gifts from the past. Consider the immense legacy left by our ancestors: those who sowed the first seeds in Mesopotamia 10,000 years ago, who cleared the land, built the waterways and founded the cities where we now live, who made the scientific discoveries, won the political struggles and created the great works of art that have been passed down to us.

The moment has come, especially for those living in wealthy nations, to recognize a disturbing truth: that we have colonized the future. We treat the future like a distant colonial outpost devoid of people, where we can freely dump ecological degradation, technological risk and nuclear waste, and which we can plunder as we please.

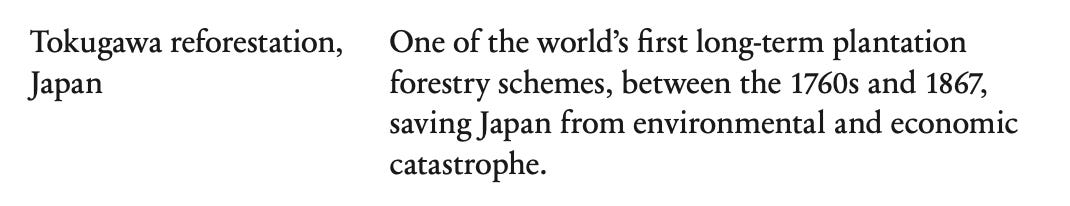

Cathedral thinking is one strategy Krznaric suggests to counter the pathological, death-dealing capitalist short-termism that infects the present. Here are four of the examples he offers out a multitude of projects that required cathedral thinking, labor and planning over a long time horizon, and immensely expansive participation. All four—as is often the case with metaphorical cathedrals—continue to have an impact, decades and centuries later, on the present.

These were just not somebody’s grand and wispy dream but projects with plans, with policy groundings, that engaged with often deeply inhospitable political and material reality. But they began with certain preconditions: social need, imagination, and vision. They began from a particular emotional positioning, a militant and resolved and generous hopefulness.

Despair and depression are cyclic, looping, paralyzing, and self-reinforcing. They are deeply understandable, justifiable responses to the state of our world. And they are, both personally and politically, highly susceptible to confirmation bias. If we accept that emotional and imaginative positioning matter in the context of achieving social change, it may be worth interrogating and interrupting our despair.

If it is necessary to act—and it is—it is necessary to think imaginatively, to think out loud and together in a vast and loose-warped weave. It is necessary to dream the cathedral. It will not come from some politician—and certainly not the current bench of multimillionaire Democratic old heads. It will come, if it does, from activists, workers, policy designers, ordinary people, artists, thinkers, all speaking together across time and space.

For myself, when I see the explosion of mutual aid organizing, the uprising of the summer of 2020, the honeycomb of autonomous communitarian structures forming in cities I know, good and intelligent journalism and public thinking articulating what needs to be done, good art that gifts the future by engaging intensely with the present, legislation that harnesses government’s power to actually protect its people, actions against predatory real estate, policies that will move us towards decarbonizing our economies, a millions-strong movement for a free Palestine, I feel profound hope. I see people holding bricks, cutting glass, getting ready to pour parts of a foundation.

five: on cynicism, in clarity

There are two things that I feel to be missing in a terrible and searing way in our body politic.

One is the absence of a widely articulated cathedral: inspiring, universalist, humane, morally clear, bestowing of a muscular and participatory hope. Which is to say, bestowing to the many of the infinite opportunities to help build the structures we need.

The other is a lack of practice in the various penmanships of togetherness. Of being with and acting with other people, notably people who are different from us. Of working in tandem with our people to achieve our desired lives, to say nothing of our desired politics.

These are things that we can work on.

I can imagine a cynical read of anything I’ve set down here; when I was young enough not to know any better I was a cynic.

Kings and fascists dreamed of cathedrals too. I can’t emphasize this enough: the essential mechanism of cathedral thinking is value-neutral. Here’s an example of what I mean:

About three and a half decades ago, capital and anti-democratic interests joined together and practiced their own politics of the visionary possible. A 1970s cabal of babyfaced conservatives—headed by a young Mitch McConnell, fun fact— wished to remove almost all constraint from corporate and private money in politics, and we ended up with Citizens United and industry-lobby-castrated politicians like Joe Manchin.

Their result, the nave and foundation stone of the cathedral they helped built, is impressive. An awe-inspiring upward transfer of wealth from the many to the fewest few. Gerrymandered maps and strategic voter suppression. Forever wars and private prisons and immigrant detention. Among much else.

The truth is just this: the political future is unaccountable, antiknowable, and far more malleable than any comfortable cynic would wish you to believe. The future, very simply, belongs to power, which is subject to its own shocks and successions.

“Vietnam is free—free of the Japanese, free of the French, free of the Americans, free of the Chinese, free of the Cambodians. Vietnam, once a synonym for endless war, is at peace.”

- Maxine Hong Kingston, 1997

The imperative of a well-articulated cathedral from the left, accessible and universalist enough to capture the imagination and desire of masses of working people, is made all the stronger by the fact in in its absence it is the cathedrals of hard-right fascistic imagination and desire we will be entombed in.

To choose nihilism is to participate in the continued colonization of the future.

six: in conclusion

One of the fundamental ordering patterns of human life, ecology, markets and industry is the S curve, or sigmoid curve, which can be summed up as: nothing grows forever. For every boom, a bust; for every period of flourishing a period of decay.

The order we have lived under is coming to a close.

We now get to ask ourselves some things. What is the world you want to live in? How do you want your workplace or city or town to function? How can we reach and persuade the unpersuaded? How can we neutralize our enemies? What rights are denied people you care about? What should be valued besides profit at all costs? How might things run, then?

We are in deep debt to people who asked themselves, then others, these questions, and then dreamed, and then acted. We owe the practitioners of universalist, humanistic, cathedral thinking and ancestral thinking—people who lived during times far more brutish and death-filled than ours—quite literally, our lives. We owe them vaccines and sewer systems and public schools, bills of universal rights, the freedom to love across the faultlines of race and gender. Among much else.

“The only choice we have as we mature is how we inhabit our vulnerability, how we become larger and more courageous and more compassionate through our intimacy with disappearance, our choice is to inhabit vulnerability as generous citizens of loss, robustly and fully, or conversely, as misers and complainers, reluctant and fearful, always at the gates of existence, but never bravely and completely attempting to enter, never wanting to risk ourselves, never walking fully through the door.”

- David Whyte

The goal, in my eyes, is not about achieving the commonly understood meaning of utopia, which carries the subtext of the unrealistic naive dream, not what the Greeks called outopos, which means the place that cannot be.

What is at stake is eutopos: the good place. Built in sections, over decades, if not a good part of a lifetime, with steadfastness and stamina and will. Eutopos. It is what we owe each other, what we owe the Earth, what we owe our good ancestors, and what we owe those yet to come. Eutopos. It is still possible. It has always been possible. There is a lowering window for its possibility to be realized.

The window is open, still.

Once upon a time I was a liberal; I used to write any politics-touching nonfiction in the language of exhortation and appeal; in a register of earnestness and alarm. I guess what I have now instead is fury, resolve—and a certain, roving, evaluative Sauron’s-eye of calculation/imagination. The eye looks inward, and beyond.

This newsletter installment is part of an ongoing series on American politics. When the series is complete, it’ll be made available as a sequence of printed and designed zines. If you liked this, feel free to share it with other people, to subscribe to this newsletter as a free or paid supporter, or check out my novel All This Could Be Different.

This kickstarted some big thoughts. Will definitely bring the idea of “cathedral thinking” into future community discussions here

This reminds me of Foucault's essay, "Of other spaces", which if you haven't read yet, you should. He makes the point that certain places, church graveyards are his example if I remember correctly, heterotopias, are structured differently: our duties, responsibilities, and temporalities are so different in these places as to allow us to imagine different possibilities for existence there.

In a hard to find essay (in the journal Raritan, I believe), Patrick Murphy argues that universities could and should be one of these places. They disrupt the normal rhythms of life and might help us imagine life outside of capitalism.

I love this idea though: cathedral-thinking as a way to reorganize the collective imagination.