Discover more from thot pudding

living in interregnum: the context and the coconut tree

j*e bid*n, the levers of power, letting elite gossip be elite gossip, gramsci, the work ahead

“Interregnum was the term used in ancient Rome to refer to the moment of legal and political in-betweenness that followed the death of the sovereign…The ruling order had lost its capacity to lead through consent. The masses had drifted away from traditional ideologies and toward a structure of feeling that awaited full articulation. The horizon was open.”

- Andrea Muhlebach

Years ago, when Shyamala Gopalan Harris told off her daughter for being, essentially, an ahistorical yute, she had no idea that her words, quoted decades later at a White House event and then memed and beamed around the world, would take on the unhinged, irradiated half-life that they have.1 “You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?? You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you.”

Alas, Americans, largely speaking, are the most incorrigibly, irrepressibly, coconut-tree-ass public imaginable. In the wake of Recent Events, I wanted to write to you about five things I’ve been thinking about, all connected: the question of the Democratic nominee for President, why ordinary people could disinvest from obsession with this question, one way to reframe the moment we are living through, Pr*ject 2*25, and the actual levers of power and change.

It’s a piece of writing that is…not short 😈..but pretty readable, that deals with both the present moment—the coconut tree, if you will—and the *dons clown nose* the context of all in which we live.

the coconut tree: a recap

Two weeks ago, I tuned into the first Presidential debate, aware of the Biden administration’s wins on behalf of working people and the environment2 and deeply apprised of its grotesque failures, like its contributions to Israel’s ongoing genocide in Palestine. But no actual policy discussion was had that night. No vision for the future was discussed. Even if it had been, nothing could mask the overwhelming optical narrative that emerged.

Trump was appalling: lying, fascistic, crude, xenophobic, cruel, kind of funny. But watching Joe Biden, who appeared incontrovertibly old and frail—slack-jawed, cotton-voiced, eyes popping with shock at a long-known liar’s lies, I felt a level of doom that I hadn’t in a long time, given the stakes of November’s election. I sensed my own powerlessness suddenly and acutely, and that is not how a winning politician makes anyone feel3.

The second the debate was over, there was blood in the water. The liberal pundit class finally turned on Biden, with multiple prominent voices and outlets calling for him to step down. A series of damning reported pieces about his decline and careful management by his aides to conceal this have since been published. Online, people have been posting! through! it! Strategists, some professional, some armchair, have suggested a variety of approaches and responses, ranging from sitting tight and standing by “our” man, to suggesting Biden step down and sub in Kamala Harris, to orchestrating a new candidate being chosen via mini-primary during the Democratic National Convention in August.4

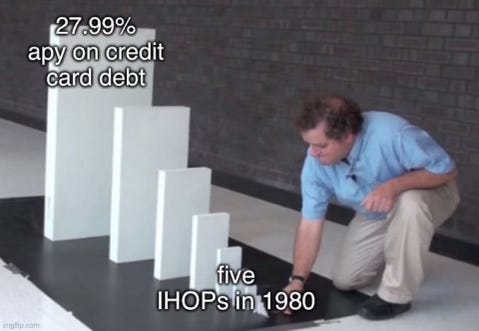

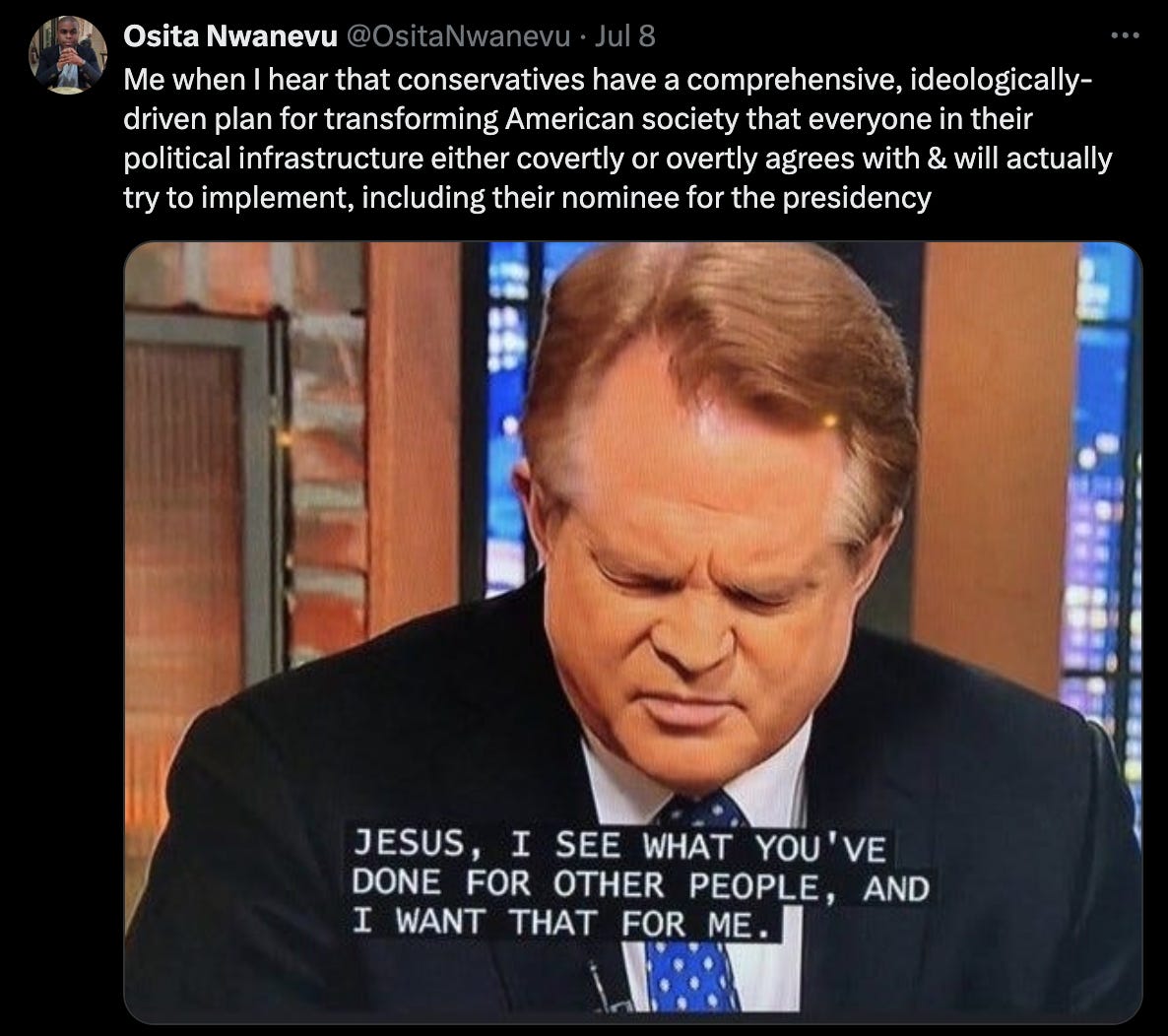

It’s not all about the election. The Supreme Court’s Trump-selected majority of conservative justices seem to be getting their Adderall okay despite the nationwide shortage; it’s been a very productive (cataclysmic) past two weeks over there.5 Now there is (finally) a slowly-increasing mainstream awareness of Project 2025, a mammoth transition document led by The Heritage Foundation that lays out a right-wing plan to transform the U.S., under Trump, into a conservative Christofascist state.

The wolf is at the goddamn gate, I thought, reading large parts of it and also summaries of it, over the past year, in calm despair. What I was reading represented a functional repeal of a past century’s work of progress on racial, gender, civic, and sexual rights that would reshape the country. Kevin Roberts, who leads The Heritage Foundation, has said in public that the organization’s key function now is enshrining and institutionalizing Trumpism. “We are” he said, “in the process of the second American Revolution, which will remain bloodless if the left allows it to be.”

Every day that has passed since the first debate I’ve seen waves and eddies of discourse re: What To Do, most exclusively and myopically focused on the question of whether Biden should step down, and who could replace him if he did.6 I’ve found persuasive Osita Nwanevu’s framing: that the Democrats don’t (just) need a new candidate, they need a reckoning.

Let’s imagine Biden stays in it and (somehow) wins in November, or that another Democratic nominee is chosen and wins in November. Biden’s (characteristic) response to SCOTUS’ recent Trump immunity ruling, the ruling that announced that a President could have many of the powers of a king, was to…verbally disapprove. To tell people to vote harder. To echo Justice Sotomayor in saying, “I dissent.” You dissent??? Bitch????? What will the actual plan be, from this party who of late has been annually publishing the handbook on toothless handwringing? For this captured and corrupt SCOTUS, for Gaza, for Roe’s repeal, for the various parts of Project 2025 that are even now, slowly being put into practice through a right-wing-captured judiciary???

But it’s not just the Democratic Party apparatus that requires a reckoning.

the context: let elite gossip be elite gossip

First things first: if you’re feeling anxiety or dread about the question of the Democratic nominee, you can, if you want, free yourself. There is something liberating to be found in asking, in succession: What is the actual nature of the situation I’m considering? and What power do I actually have, within it?

Because you, unless you are in fact a political power broker, a truly well-platformed journalist, or a DNC delegate—as a tiny handful of people who read this newsletter are (good luck, babes!)—you, and most of us, do not have, at this stage, any power to affect who the Presidential nominee is. Absolutely none. Flood of news stories and horse-race-polling and celebrity op-eds notwithstanding.

There is freedom in calling palace intrigue and elite gossip for what they are, and saying, well, this has nothing to do with me.

the real context: we live in interregnum

The second American Revolution, which will remain bloodless if the left allows it to be. The actual nature of the situation that we’re considering is that in January 2025 we are likely to see either a full-fledged authoritarian bent on revenge and reconstruction in the White House, or a potential attempted overthrow of an election by right-wing force—and there appears to be no plan yet to deter or prevent this.

It’s that we are living through the early stages, and approaching the cliff, of a sixth extinction.

It’s that millions of people, especially young people, have experienced the lacerating moral injury of witnessing the mass slaying and torture of Palestinians with their tax dollars and finally see the contradictions at the heart of the rules-based order.7

It’s a time of interregnum, in other words. Writing from a Fascist prison in Italy, reflecting on his nation’s interregnum, its period of political transition, Antonio Gramsci set down these words: “Il vecchio mondo sta morendo. Quello nuovo tarda a comparire. E in questo chiaroscuro nascono i mostri.” This was translated, loosely and famously, as

“The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.”

A more faithful, less pithy rendering would say something like, “The old world is dying. The new world is slow to appear. And in this chiaroscuro (light-dark) emerge monsters.” The academic Andrea Muhlebach contextualized this further:

“Interregnum was the term used in ancient Rome to refer to the moment of legal and political in-betweenness that followed the death of the sovereign and preceded the enthronement of his successor. The declaration of interregnum was accompanied by the proclamation of justitium, for it was not only sovereignty but also legality that was suspended.

Gramsci brilliantly played with these terms, extending them as he grappled with the generalized crisis of authority in his own time. Old hegemonies were crumbling. The ruling order had lost its capacity to lead through consent. The masses had drifted away from traditional ideologies and toward a structure of feeling that awaited full articulation. The horizon was open.”

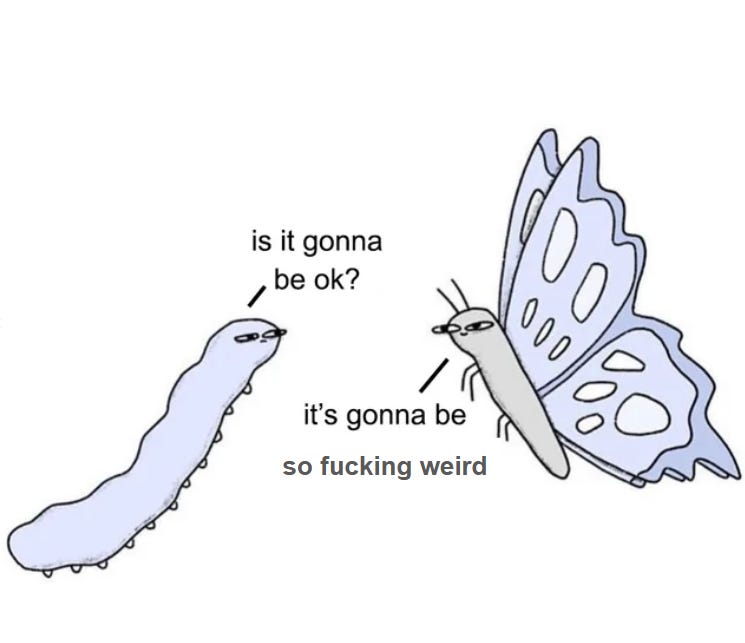

We too, now, are in interregnum, in the chiaroscuro, a time of interplaying light and shadow, hoping to keep shadow from overwhelming us. We are living our lives, where many of us are still allowed full distractions and partial freedoms, while sensing the wolf at the gate. We sense that our ways of life and our limited ways of acting politically may be coming to an end, one way or another.

What that televised debate two weeks ago ushered in was the sudden mass sensing that we are in interregnum at a level both individual and system-based. The sovereign is dying, functionally speaking. Legality is uncertain; justitium, or suspended law, hangs over us. Monsters have emerged, and continue to. And a new world is slow, slow, slow to appear.

the really real context: the levers of power

Let’s pull all the way back to fundamentals. We don’t love the world as it is right now; a lot of it sucks absolute ass. Most of us want a new world: a changed one, a decent one, a survivable one. Most of us, also and crucially, do not want things to get worse: more cruel, more authoritarian, less democratic, less livable.

So, this is how I think about making change.

A changed world is birthed through the sustained and robust exercise of power. On occasion it’s made through the speedy rearrangement of power and resources in response to a shock event. Superstorms wreak destruction, technologies like AI or the mobile phone have their viral and reformatory spread, crops fail, plagues decimate populations: these are examples of shock events that power responds to, or is bested by. Shock events are not levers of power; they are opportunities power can exploit, or liabilities power can outmaneuver.

There are four fundamental levers of power theoretically accessible to the people.

One is cultural: persuasion of the masses, persuasion of elites, or both. (Elites and the mass, as we know, exist in an uneasy relationship of dependence. When you say you hit two birds with one stone, you’re either working with a notably large stone, or using the force of the first bird to hit the second.) The lever of culture can look like: corporeal speech like mass protests, conversation-shaping digital virality, people choosing different ways to live on a mass scale, the seeds of new ways of thinking in novels or poems or books, or shifts in depiction in TV and film.8

Another lever is electoral; at least, this is true within functioning democracies. Elected representatives pass legislation that is codified into law, continually modifying the living architecture of a society with respect to its ordering of capital and labor, its social compacts, its relationship to the earth, and its composition. The electoral lever was responsible for the New Deal, the ADA, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and more. In the United States, the lever of electoral power is complicated and compromised by: the influence of corporate lobbies, the existence of antidemocratic institutions and practices like voter suppression and the Senate, and a system where only two parties can access governance.

The third is economic: deprive capital of its ability to grow or simply threaten to, most ordinarily with tactics of refusal and sabotage: the strike, the boycott, or physical blockages to the flow of commodities. (One example of the latter is the weapons blockade erected by pro-Palestine activists at Tacoma Port in November of last year.) The economic lever is incredibly powerful when activated. It is also difficult to sustain for a range of reasons. Including, but not limited to: our high cost of living that requires most people work long hours to have shelter and food, our hyperindividuated and consumption-addicted culture, our ever-more-punitive police and prison system, and, sure, the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which was passed in retaliatory response to 4.3 million American workers striking during 1945-46.

The fourth lever is force. Guerrilla war, the killing of elites, the capture of civilians, intentional property damage for a cause—this is is a non-exclusive list of examples. Historically, violence against people (versus property) has historically been the option both most difficult to ignore and most difficult to contain; it frequently rebounds and metastasizes; it often has its own long, grimly radioactive half-life. When wielded by the people against a state, the use of force is often dwarfed by the retaliatory violence and power of the state, which like any institution works to protect itself at nearly any cost.9

Cultural, electoral, economic, and force-based: historically and presently these have been the people’s actionable levers of orchestrable change. To be successful, they need to be used by a collective, not merely at an individual level; the Uncommitted Movement, for example, used the electoral lever in a far more effective way than if a handful of people had acted individually and without coordination.

Also, the levers often are necessarily used in joint combinations. The 2010s wins of the gay rights movement were fought for over decades by activists who worked on cultural, economic, and electoral fronts. South Africa’s successful anti-apartheid movement used the levers of culture, economy, electoralism, and force—uMkhonto weSizwe, the ANC’s paramilitary wing founded by Nelson Mandela, engaged in property damage and bombings to advance their cause.

Almost always, when the levers are less than effective it has been because they are unstrategically or insufficiently harnessed by people against the ruling class that sets the status quo.10 A single lever is almost never enough, particularly the single lever of culture or the single lever of electoralism.

There is one lever I haven’t yet discussed, because it is not meaningfully available to ordinary people. It’s the single largest driver of the elite capture of American governance: lobbying and lobbying-adjacent elite activism. Meaning, the practice of individuals and corporate entities influencing government representatives. This can look like meetings, conditional funding, coordinated model legislation, and elites (including corporate representatives) organizing to capture divisions of government through networked influence. Leonard Leo’s Federalist Society, for an example of the latter, is responsible for six out of six conservative justices on the current Supreme Court.

What has most transformed American governance in the last three decades is lobbying and lobby-adjacent activism, which is essentially highly organized elite-to-elite persuasion that fuses the cultural and electoral levers of power, while bypassing the people.

Elite capture is a bipartisan practice, though it has been practiced more efficaciously and with more stamina by the right wing—while the left wing won cultural victory after cultural victory. It is responsible for the mess we are in today in approximately a thousand ways.

Which brings us to—

a coconut tree, with context: project 2025 and differential fascism

There’s a certain kind of scorn I see from parts of the online left for people who are deeply fearful about Project 2025 that I think is unwise, if understandable. The scorn is, in part, a contrarian “you don’t scare me,” and, in part, also is identifying something true, which is that that in in important ways, fascism is already here, and for some groups of people it has always been here.

So to expand on the metaphor: a growing number of people who have lived within the freedom and abundance of the liberal order, now see the wolf of a fully realized fascism at the gate. And also, the wolf has been prowling through the village and woods, preying on others considered expendable by those in power, and nothing was done.

The writer Alberto Toscano talks about this phenomenon in his articulation of “a differential experience of fascism.” He writes that “within polities which might ordinarily appear to be liberal there can also exist large pockets or enclaves or social areas of control and domination that could with some legitimacy be called fascist.” He speaks of police terror against Black people in the U.S. as an example of this, and also cites the historical example of settler-colonial societies broadly.

What reading writers like Toscano and Angela Davis and George Jackson helped me comprehend was that we have lived always under a dual state: the quiet often-unspoken understanding that in our society—even in times when liberals hold power—there are in-groups the law protects and does not bind, and out-groups the law binds but does not protect. (Some of the out-groups, in this country’s history and present: Black people, queers, Indigenous people, Japanese people, Muslims, Arabs, South Asians, trans people, disabled people, women.)

In-groups the law and state protect and do not bind. Out-groups the law and state bind but do not protect. What left movements in America have fought for throughout its history, sometimes triumphantly and beautifully, is the continued movement of people from the second category to the first.11

So, yes, it is factual that right now, Democratic mayors are building Cop Cities and cracking down on left activists with extraordinary force. Because of a conservative SCOTUS’s repeal of Roe under a Democratic President women in red states are being airlifted to neighboring state hospitals because they cannot legally terminate even pregnancies that are about to kill them. The dual state is operational already; we see it in evidence around us.

But none of that, to me, means that we should take less seriously a plan to deepen the dual state into a full-fledged fascism, to repeal a 20th and 21st century’s worth of rights and progress, and to reshape the country’s governing apparatus in totality. Project 2025 proposes a lot, and you can read about it in more detail here. But to give you a refresher (or introduction), it lays out a detailed roadmap for:

replacing thousands of civil government employees with Trump loyalists and proposes that the entire federal governmental apparatus, including independent agencies such as the Department of Justice, be placed under the direct control of the President;

eliminating or functionally eliminating multiple agencies and legacy government programs, like the EPA, the Department of Education, Social Security, Medicare, Head Start; also it would severely limit food assistance to 40 million households currently receiving it;

dramatically increasing funding and power to the Department of Justice, increasing the punitiveness of said DoJ (death penalties, maximum sentencing), and directing said DoJ to pursue Trump’s adversaries (and likely left protestors) by invoking the Insurrection Act of 1807;

cutting federal dollars for research and investment in renewable energy, removing all carbon-reduction goals and monitoring, and increasing fossil-fuel energy production—all reforms that would result in the overshooting of the livable window of planetary warming;

withdrawing the abortion pill mifepristone from the market nationwide, thus outlawing the method most commonly used to terminate early-stage pregnancies, and accounting for about 40% of abortions;

repealing major provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ending public service loan forgiveness, eliminating full employment as an economic goal, defining the married heterosexual nuclear family unit as the only acceptable way of life, outlawing pornography including presumably sexually explicit art, eroding the protections of no-fault divorce; and

grievously stigmatizing queer and trans people—denying us healthcare, disrespecting and eroding protections for gay marriages and adoptions, associating trans people with the sexualization of children, and making all of us more vulnerable through the stripping of anti-discrimination protections at workplaces and schools.

This is worth mobilizing against in the years to come, and it is worth mobilizing against with force and toughness, with large numbers and diverse tactics, with organization and moral nerve.

coconut tree, context, and conclusion: electoralism will not save us vs the chomsky take, using all the levers available to us, the will to live

In the American left and also broadly among younger people, over the last five or so years, there has been a rising flank that says some version of, “electoralism will not save us.”

To engage with this with intelligence and subtlety would take an essay all its own, but what I will say is that this is a viewpoint I am sympathetic to, and sometimes in cautious agreement with, while also observing that no one is defining what “electoralism” actually is or means.

Inasmuch as the statement refers to the brokenness of the current two parties and the practical impossibility of a third party emerging, I am in agreement with it. But it is worth saying that at least some people say this or things like this as a shield disavowal for the left not having worked hard enough or in ways that are resourced enough to persuade a sufficient mass of people to our causes, candidates, and movements. A lot of people choose not to see that many of the left’s stances have simply not (yet) been adopted by a critical majority, and that more persuasive work and organizing could and should be done before announcing defeat.

Electoralism will not save us. Well, what does it mean to be saved, I ask in loving exasperation. For myself, I see the electoral lever as one of four available to ordinary people, and as one of five available to the left wing, which has its leaders and cadres too, just in a more anemic form. I am in many ways of the old-school left, which leaves me sympathetic to what we can call the Chomsky take:

Well, there is a traditional left position, which has been pretty much forgotten, unfortunately, but it’s the one I think we should adhere to. That’s the position that real politics is constant activism. It’s quite different from the establishment position, which says politics means focus, laser-like, on the quadrennial extravaganza, then go home and let your superiors take over.

The left position has always been: You’re working all the time, and every once in a while there’s an event called an election. This should take you away from real politics for 10 or 15 minutes. Then you go back to work. The left position is you rarely support anyone. You vote against the worst. You keep the pressure and activism going.

- Noam Chomsky, in 2020

We can agree emphatically that voting alone, especially now, is nowhere near enough to keep the wolf from the door. But the idea that it’s a lever not worth employing at all is untenable. I still think of what might have been if SCOTUS had not helped George Bush—father of the forever wars—steal an incredibly narrow election win from Al Gore, climate champion, all the way back in 2000.

What is painful to say is that the American left—outside of the resurgent power of labor unions, and the solidarity movement to free Palestine—is disorganized, atrophied, unmilitant, and uncertain, much more so than it was in 2020. It has relied heavily on the cultural lever and a generalized ethos of refusal and righteousness. It currently has no unified and articulated cathedral of belief to rally people around. It sure as hell has no equivalent Project 2025.

If you are American and reading this, my personal opinion is that your hands are no cleaner because they don’t touch a ballot or a phone-banking app or the number of your relative in a swing state. We live under and within empire. Empire that, if it continues as it is, will likely boomerang back to us in the long future, especially since we live on an overheating planet, in a society experiencing various kinds of slow social collapse. So to me, it makes sense to try to prevent this. To do everything we can, both in the now and in the future, to withdraw from wars, to codify rights, to abolish the power of the prison-industrial complex, and to protect the planet from human-caused ecological catastrophe.

I mean, I say all this, but do what you want and what is right for you. Truly. The way I think is the way I think, and you don’t have to think like me. Do your own thinking; borrow mine to the extent it is useful.

The way I think is, if the wolf is at the garden gate, you do everything to keep him from your family in the house. You can lock the door. You can call for help if there’s someone to help you. You can get your gun.

And in fact, you can do all of this.

We can do all of this.

We can say, no lever of power should be untouched in the race to survive, to guard our rights and freedoms, to protect ourselves and ours. We can tune out of palace intrigue and elite gossip and turn our energy to where it counts. We can recognize that we often needfully plan the work of politics using the unit of years, not months, as our enemies do. We can comfort individuals who are rightfully and understandably fearful for the future by bringing them into the fold of the collective; collective fear and the organized mobilization that can result from it is is a potent thing. We can, sure, fine, as needed, take fifteen minutes in November—to participate, to vote, or to persuade people in key states to mobilize, whatever is a better use of our time—and then get back to the work.

The work is to see the truth, which is that we live in interregnum, and the horizon is (still) open.

The work is recognizing that whoever occupies the Presidency of this country in 2025 will likely be a species of an enemy of the people, and that we can be strategic even about our choice of enemy.

The work is helping build and expand a left flank that is worth being part of, which to me means, living up to the right’s boogeyman depiction of what the left is: organized, powerful, disciplined, persuasive, and collective. Hell-bent on curbing the ravages of capital, of fascism, of police and prisons. Offering new freedoms and belongings and ways of living to all. This kind of building and expansion can happen through cultural work, through organizations, through vibrant movements, and through exercising most or all of the levers of power. It would help, I think, for this left flank to be inviting—tough, thoughtful, joyful, unfragile, punk, nurturing to its members, capable of meeting a vast range of people where they are and then making the case to them for a new world and a different way.

The work is surveying the truth of the country we live in, with its startling beauties and its history of differential fascism that stretches from its founding, and thinking about what it would mean to not merely keep the wolf from the house, but end its reign of terror for everyone.

And the work is to say, until it lives within us as steadfast and militant orientation: I want to live. I want those I love and the Earth I am part of to live. I am a unit of power, and every person I know and meet is a unit of power. The long future is unknown and unaccountable, and until it is fully known I will not stay afraid; I will not prematurely give up. Even when grief and fear come I will not forget I belong to other people. I want to live, with dignity and joy, as long as dignity and joy remain possibilities, and I will. I swear I will.

This newsletter installment is part of an ongoing series on American politics; you can read a companion piece here: Building The Cathedral: Notes On Politics And Vision. If you liked this, feel free to share it with other people, to subscribe to this newsletter as a free or paid supporter, or to check out my novel All This Could Be Different.

Harris’ mom’s words have been referenced by now in Charli XCX and Lana fancam remixes and thousands of TikToks and tweets. This recent memeification-as-tentative-coronation of Kamala Harris as the potential savior of the Republic is the newest turn in our hallucinatory chapter of American politics, turbocharged by Joe Biden’s nightmare debate performance.

I thought in particular of the Administration’s landmark Inflation Reduction Act, which even in its diminished-by-Joe-Manchin form, is projected to reduce U.S. emissions by forty percent by 2030, while investing in historically disadvantaged communities. We need more than this legislation, of course, and the death-specter of “energy independence” driven by the fear of the right wing, has compromised the IRA. But it was still enormously meaningful to me, this scale of investment and infrastructure-building, with the potential to save so many lives. Anyway, I was thinking all this BEFORE tuning in, grappling also with the horror and grief of Gaza, feeling sick about even trying to engage in this sort of moral calculus. And then I turned on the livestream and was like, oh damn he is dead dead, maybe this will be moot.

To be clear, both Trump and Biden are elderly and experiencing a decline in capacity, but only one of them has been hounded for years by a narrative that he is too old to be President.

One of the most surreally funny developments, for me, has been seeing multiple fellow former Bernie supporters claim, with some peculiar vinaigrette of irony and earnestness, that they’re down to support milquetoast, center-left, former prosecutor Harris, that given this moment of crisis they’re ready to hang up their boots and join the KHive.

SCOTUS ruled to grant prosecutorial immunity to Donald Trump (and future Presidents) for acts taken in an “official capacity” as President, which means that Trump has some immunity for his role in the Jan 6 right-wing insurrection to overthrow the government. With the cases Loper Bright, Ohio vs EPA, and the SEC vs Jarkesy, SCOTUS threw several Molotovs into the workings of the government, an arson that will trickle down to the common American in a variety of ways, including fewer protections for clean air to breathe and unpolluted water to drink. And with the notably cruel Grants Pass v. Johnson, it ruled that a city can punish (i.e. fine or imprison) homeless people for sleeping or camping outside, regardless of whether it has shelter facilities to accommodate them.

Joe Biden, of course, has remained publicly defiant, but the writing is on the mf wall.

And given the history of the imperial boomerang, where the violence employed upon the colony eventually rebounds upon the metropole, they fear for the(ir own) future in a profound way.

#MeToo was the cultural lever at work; so was the antiwar protests of the Bush years; so was the hippies and free love communes; so were Will and Grace, Brokeback Mountain, and Moonlight.

The sheer vastness of this asymmetry of available force vis-a-vis the people and the state in a U.S. context, given technological advancement in warfare, is one of the reasons why I have not quite thrown my lot in with Marxist-Leninists who say that the only way forward is a revolution of armed struggle.

Examples: an electoral push without a robust cultural movement behind it. Or a strike called for on social media, without building infrastructure (strike funds, mass communications, food provision, childcare) to support the actual sustained mass participation that would register as any semblance of threat to capital. Or a cultural movement like #MeToo, where the movement’s material and legislative demands were drowned out by a torrent of individuated stories of trauma (and punishment) that perversely became mass entertainment.

This actually goes to the heart of what being a leftist means to me: to forge a “we” of humanness and belonging that is expansive and generous and freeing, to bring in those who were once out-groups into the “we” of belonging, and to struggle against the forces of power that at once consign some people to the out-groups while hoarding the profit and value of all labor.

Subscribe to thot pudding

letters and essays about fiction, power, beauty and how we live and think, from a novelist, nice things enjoyer, sometimes-organizer. "This newsletter feels like the best of the old internet." - Lit Hub

Your political writing always sizzles with sharp intelligence - it is so exciting. Fantastic work as always, STM! <3

🫡